Post 7: Serious issues in prokaryotic taxonomy 🔬

Published:

Currently, microbiologists face serious problems regarding prokaryotic taxonomy.

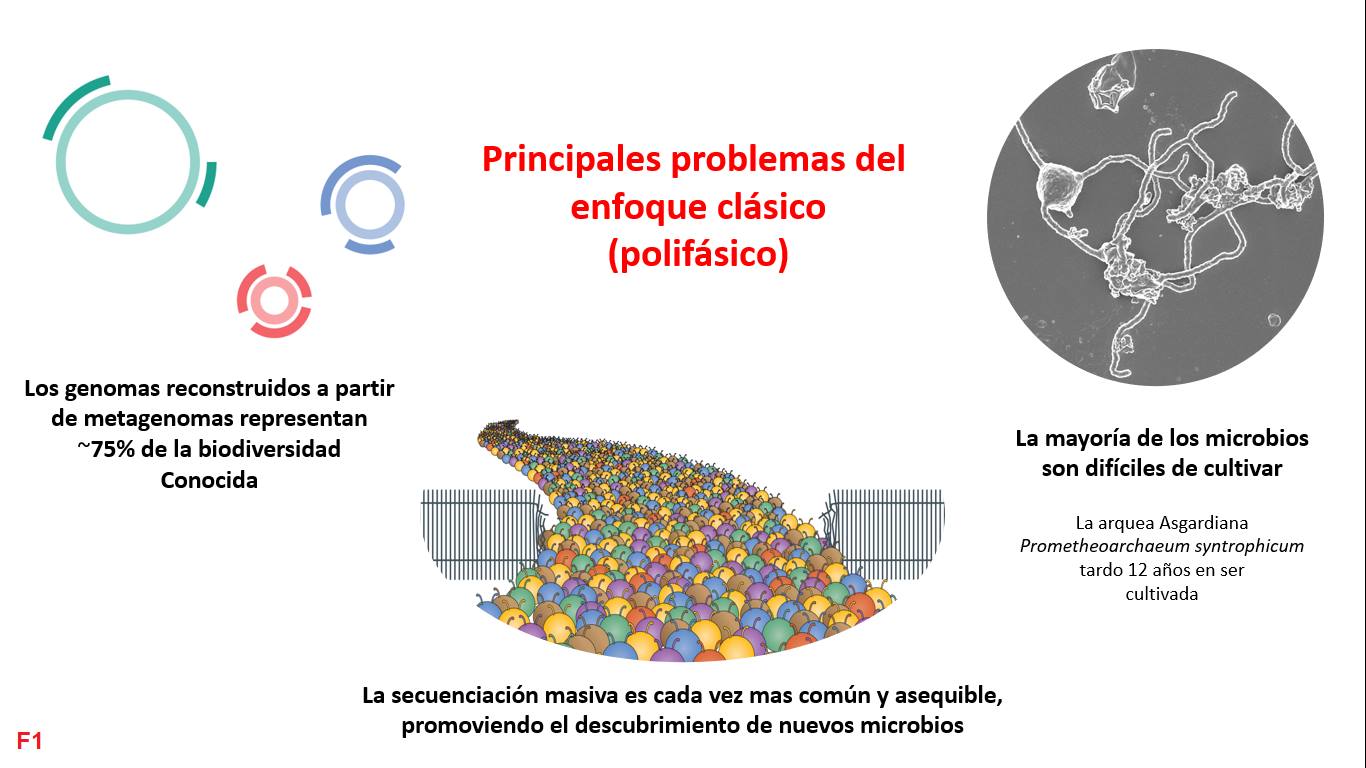

The classical way to report a new species involves cultivating it in the laboratory and performing experiments to understand its metabolism. Additionally, it is necessary to identify its taxonomy, usually using the 16S ribosomal gene or marker genes. Finally, following the nomenclature code, you assign a name and write an article with the proposal, which is reviewed, validated, and accepted once you deposit your culture in at least two international collections. The problem with this process is that it is no longer suitable for the genomic era, as the vast majority of known species cannot be cultivated (until now), some species take years to cultivate, and, furthermore, it is increasingly easier to find new species through massive sequencing (metagenomics) [F1].

In 2016, the formal proposal was made to accept genomes as ‘reference’ to name species, instead of using the method used so far which involves cultivation (polyphasic method). This led to a great discussion about whether it was better to unify all microbes in a single code, or to have a code for each type (cultivated and uncultivated).

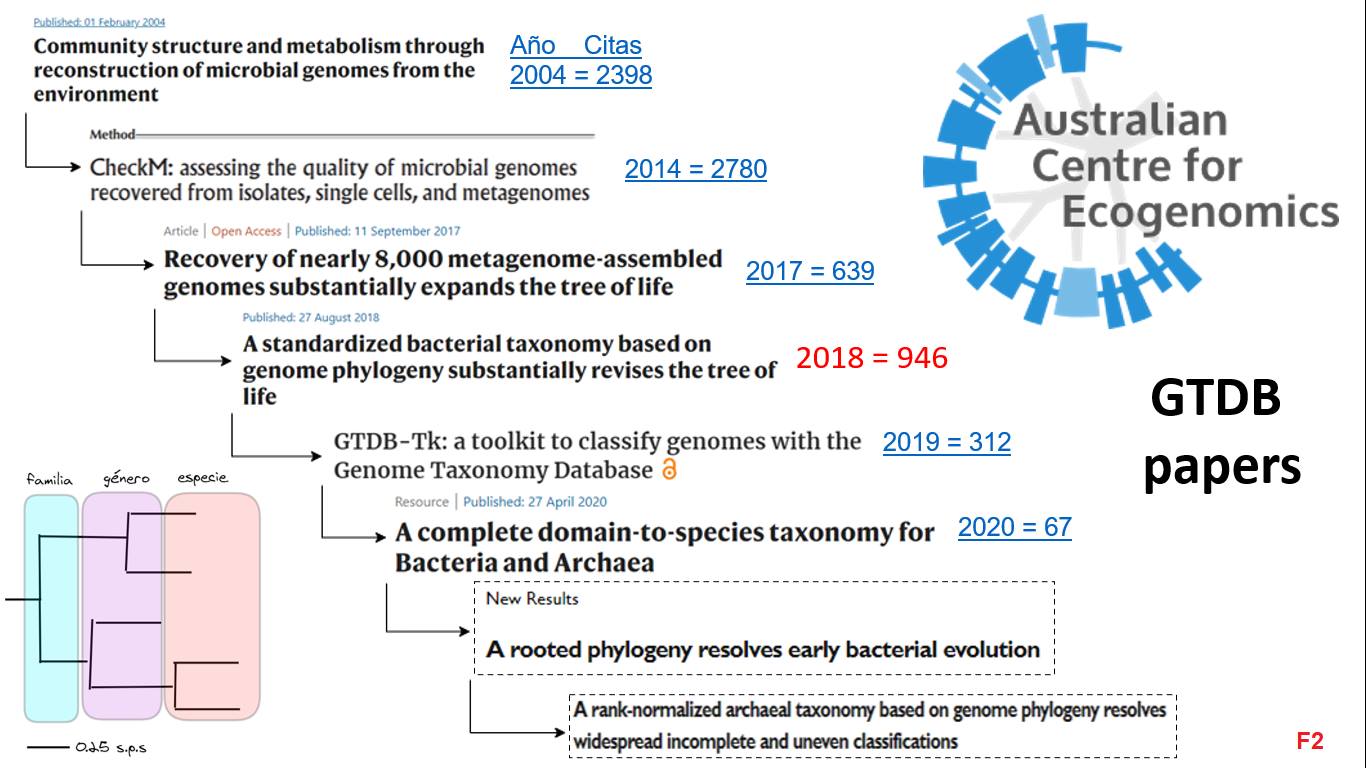

Since the 1960s, it was proposed that taxonomic categories (Family, Genus, etc.) should be assigned considering the evolutionary history of microbes (phylogeny). This and other ideas were taken up by Australian scientists in 2018 to propose a taxonomy based on prokaryotic genomes known as GTDB. To understand it well, it is necessary to read several articles [F2], but in summary: the conclusion is that many microbial groups are misclassified and also, considering uncultivated microbes, they proposed to reconfigure them into ~32,000 species of bacteria and archaea that we know through their genome.

In 2019, an independent group of scientists came to the same conclusion: classical taxonomy has many inconsistencies and needs updating; furthermore, using different methods, they observed consistency in their results regarding the Australian group. Furthermore, the methods developed seem to be useful for analyzing the evolutionary history of fungi, a group clearly different from prokaryotes, supporting the robustness of bioinformatic analysis [F3].

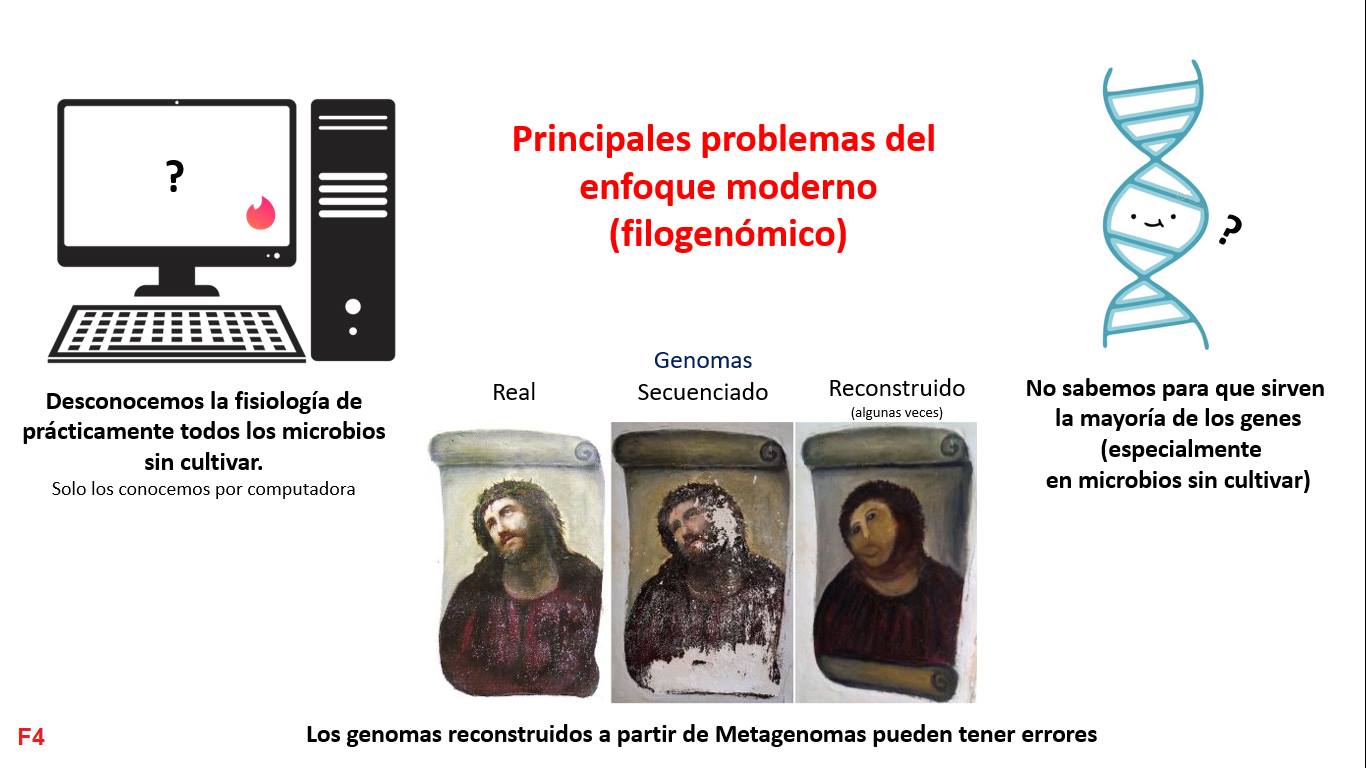

Despite everything, the proposal to update the nomenclature code was rejected just last year. Some of the reasons being the fact that genomes of uncultivated microbes are prone to errors, we do not know the function of most genes, and the vast majority of microbes lack experimental data to support their physiology. This has led to the discussion of many issues within the microbiologist community [F4].

Why does this matter? Because having a clear understanding of which group of microbes you are working with is key to the conclusions of research and enables clear communication. Personally, I lean more towards genome-based methods, but what do I know if I don’t have my biology degree yet?