Post 58: Some proteins are very strange 🧐

Published:

Reality has the whim of being complex.

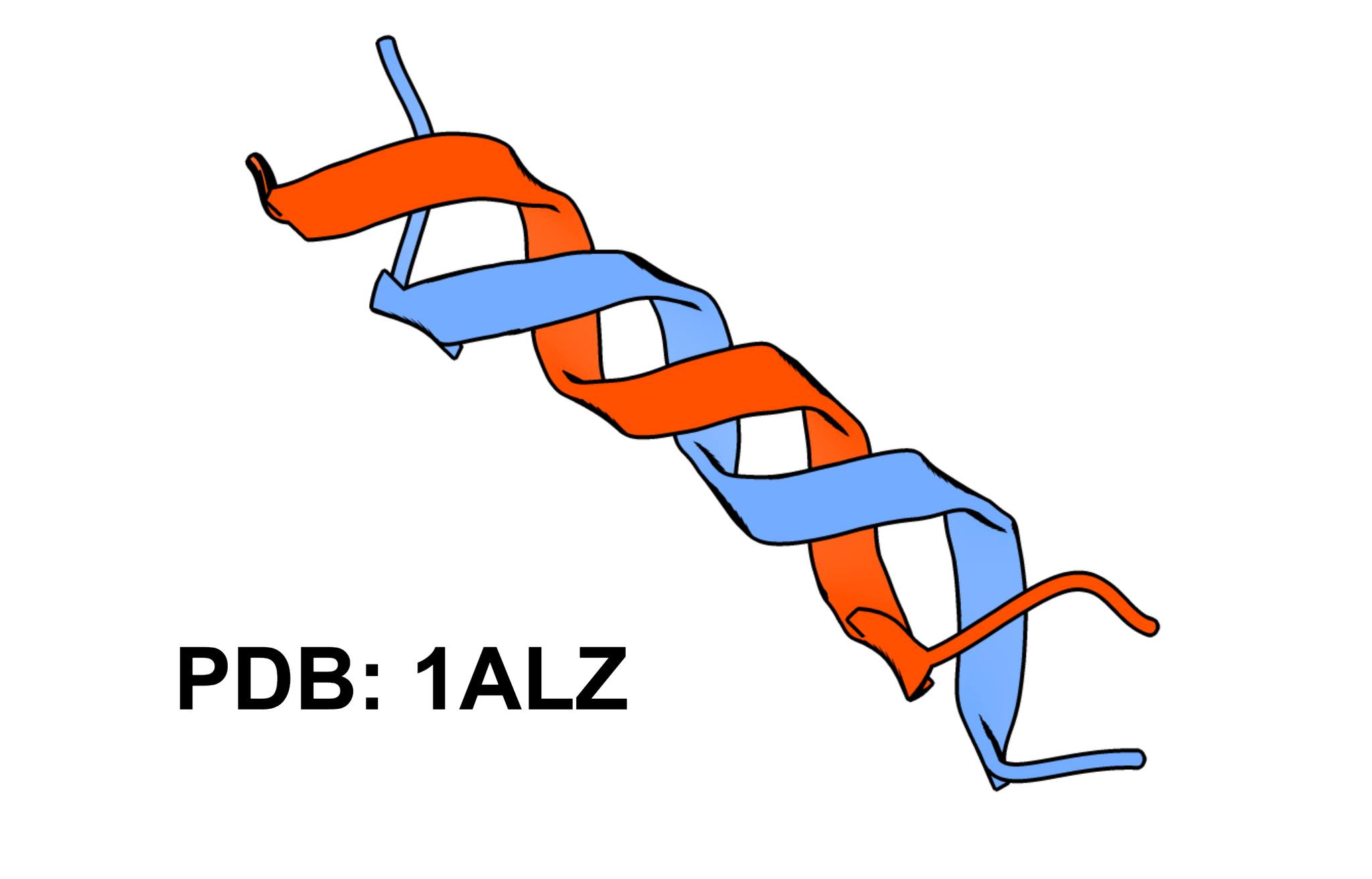

We all have in mind what an alpha helix looks like. However, if we use a mixture of alcohols as a solvent, we can obtain a helix whose folding resembles the structure of DNA. We can even find cases of helices composed of beta sheets.

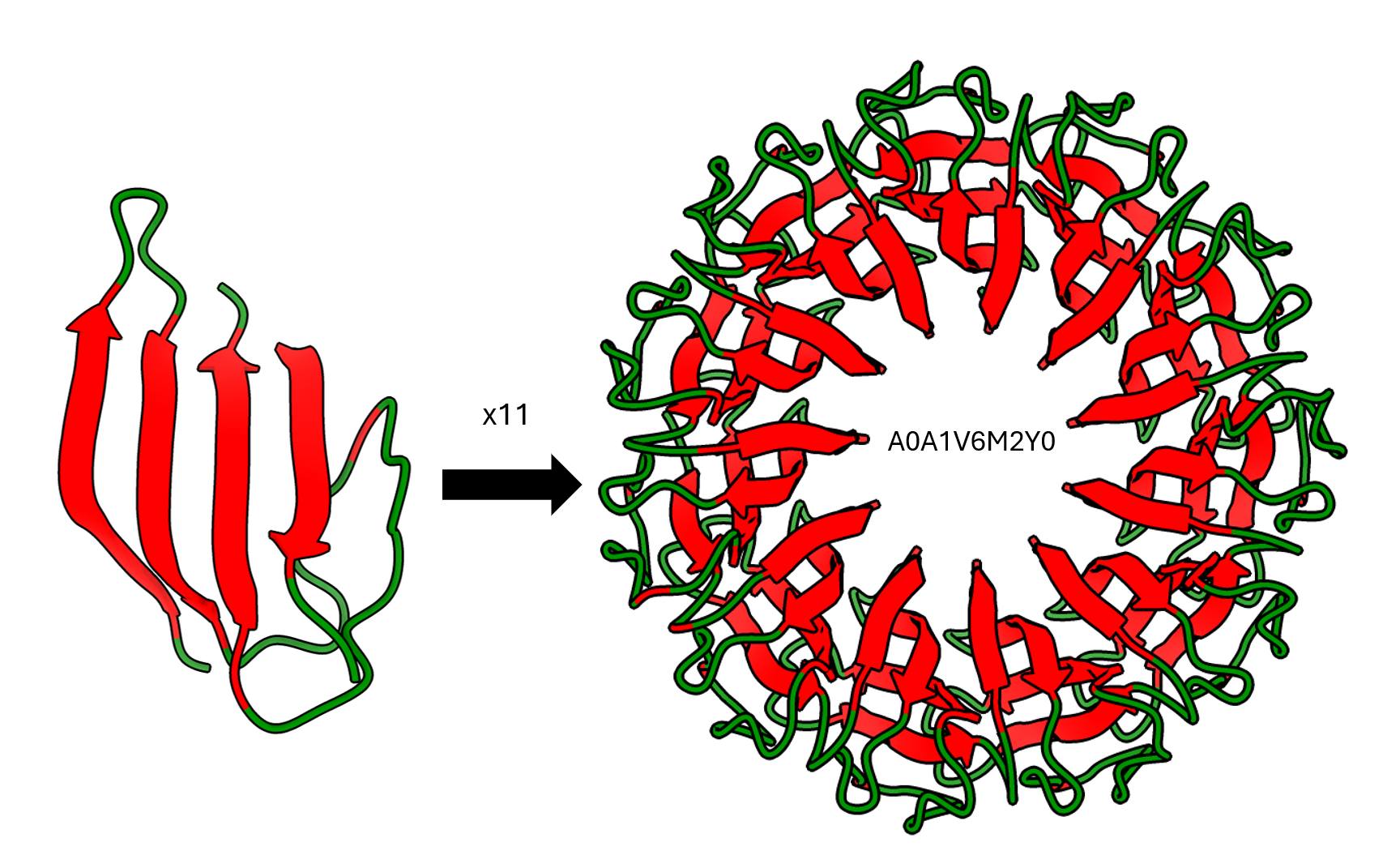

Another behavior that may seem strange is the level of symmetry in certain proteins, which can sometimes be “aesthetically disturbing.” For example, the bacterium Brocadia sapporoensis has a protein composed of 11 repeated beta sheet subunits.

But why does this happen? It is thought that primordial peptides were small and served as cofactors for ribozymes. Then they began to duplicate and oligomerize, forming peptides with high internal symmetry. They must have been peptides composed only of the 10 prebiotic amino acids, with enough hydrogen bonds to oligomerize with adjacent chains.

These were likely simple and “easy to remember” motifs that allowed them to replicate successfully, following the “laws” of memetics. Thus, the first enzymes began to emerge, as it is at the interfaces where more substrates like nucleotides and phospho-ligands tend to bind; eventually diversifying the various catalytic abilities of current enzymes through the combination of domains with mechanisms at the genetic level (like transposons and mutations) and at the protein level (like circular permutations or splicing).

From an evolutionary perspective, having high-symmetry repetitions promotes stable structures, as seen with hydrogen bonds in cyan. At the genetic level, it was easy to have a simple and small copy to repeat over and over. Moreover, due to the distribution of phenotypes, evolution tends to skew toward simple solutions, as simulated with genetic algorithms.

The presence of high-symmetry domains in current proteins is no longer as it was in their early stages. If I remember correctly, it hovers around 20% of the domains in CATH. Now we have a diversified machinery that is no longer functionally favored by symmetry. But in primitive Earth, it was. In summary, evolution took advantage of the bug 😅

And if we show the surface of the previous protein, we can see something very interesting. If evolution doesn’t plan, then why did it create a chocolate donut-shaped protein? 🤔

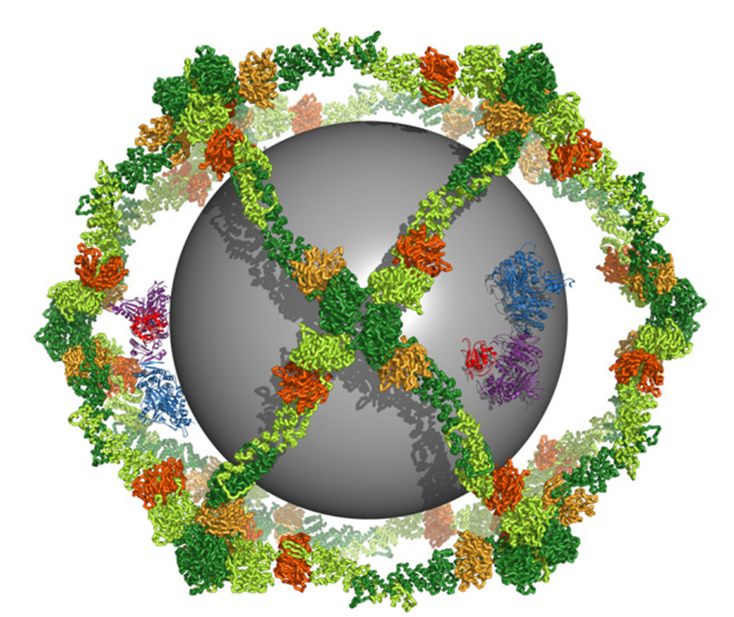

Not only that, evolution has combined domains to form quite unusual proteins. It almost seems like evolution has already built a Dyson sphere out of proteins, but since it’s inside us, busy working to keep us alive, no one pays attention to it.

Structure and Organization of Coat Proteins in the COPII Cage

As such, the domains that make up COPII do not absorb energy like a Dyson sphere. However, their architecture is quite similar. Obviously, they consume energy for translation, like everything else. Nevertheless, there are proteins that can “extract energy from nothing” (i.e., the atmosphere), equivalent to what the Dyson sphere intends to achieve:

Structural basis for bacterial energy extraction from atmospheric hydrogen

There are even proteins with very funny shapes that make me think: yes, “God” does not play dice. But he does play basketball; otherwise, why would he create a molecular hoop made of proteins? 🤨

The molecular architecture of the nuclear basket

So we better be careful with proteins (Render by Verena Resch https://luminous-lab.com/)