Post 54: How a protein shapes culture 🍣

Published:

You are what you eat and what your ancestors ate.

In biology, understanding the history of something is essential to explaining it. That’s why any biological object is “matter with history,” meaning that it’s not enough to know just its physics to understand it. The following is a great example.

In Japan, algae hold enormous cultural importance. Centuries ago, they were a kind of currency and are used in a wide variety of dishes, similar to corn or cacao in pre-Hispanic cultures in Latin America.

To degrade the cells of plants and algae, specialized carbohydrate enzymes known as “CAZymes” are required. However, we have a limited number of CAZymes, while the bacteria in our intestines have a much more diverse repertoire. In plants, the most common carbohydrates are cellulose, starch, or fructose, to name a few. In contrast, the carbohydrates in algae are different because they often contain sulfur in their structure. Therefore, the CAZymes for degrading algae and plants differ, and if your bacteria don’t have them, you end up with indigestion.

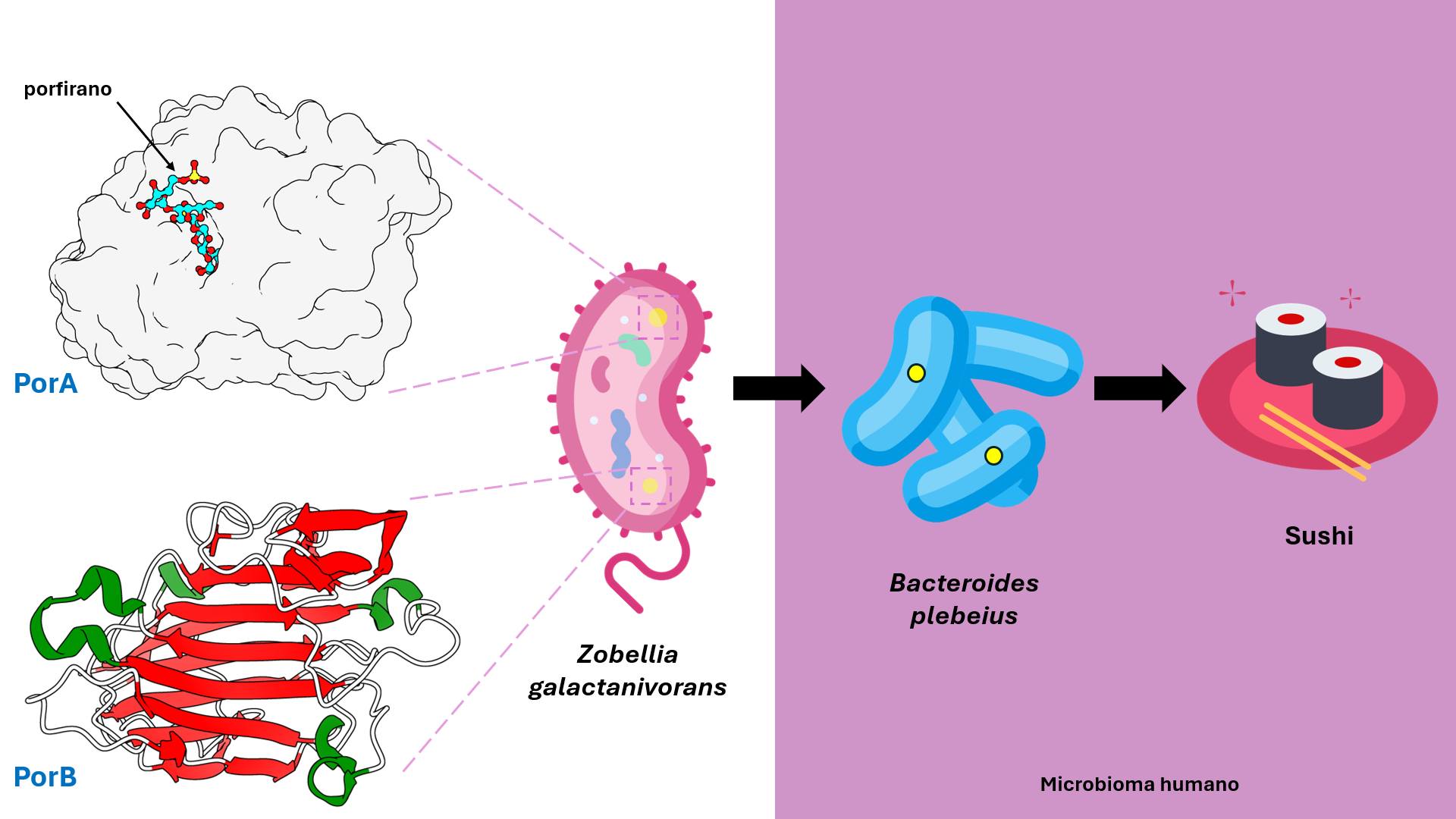

Zobellia galactanivorans is a bacterium associated with algae in the sea, and to consume them, it uses CAZymes like porphyranases (for example, PorA and PorB) and agarases. This bacterium is crucial because genetic analysis revealed that at some point in history, it transferred these CAZymes to a native bacterium in our intestines called Bacteroides plebeius. While we generally all have Bacteroides plebeius in our intestines, the Japanese have a version of this bacterium with porphyranases and agarases to degrade algae, while if we look for these enzymes in the bacteria of North Americans, we don’t find them.

Later, it was discovered that Bacteroides plebeius is one of the bacteria with the highest transmissibility between people. The interaction between mother and child is the most important, transmitting the most microbes between individuals, followed by other interactions like sharing a home or neighborhood. Thus, the ability of Japanese people to eat sushi without indigestion likely results from the transmission of Bacteroides plebeius from mother to child during their early years of life and over many generations.

Eat fruits and vegetables.

Refs:

- (Transfer of genes to degrade algae) Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota

- (On the transmissibility of bacteria and their mechanisms) The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes

- (A review on the importance of bacteria in diet) You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota