Post 3: A taxogenomic database 💻

Published:

Massive DNA sequencing has allowed us to discover prokaryotes that are “impossible” to cultivate. All these genomes are available in databases such as NCBI or GTDB, but we face a problem every time we encounter a new genome: What the hell is this creature?

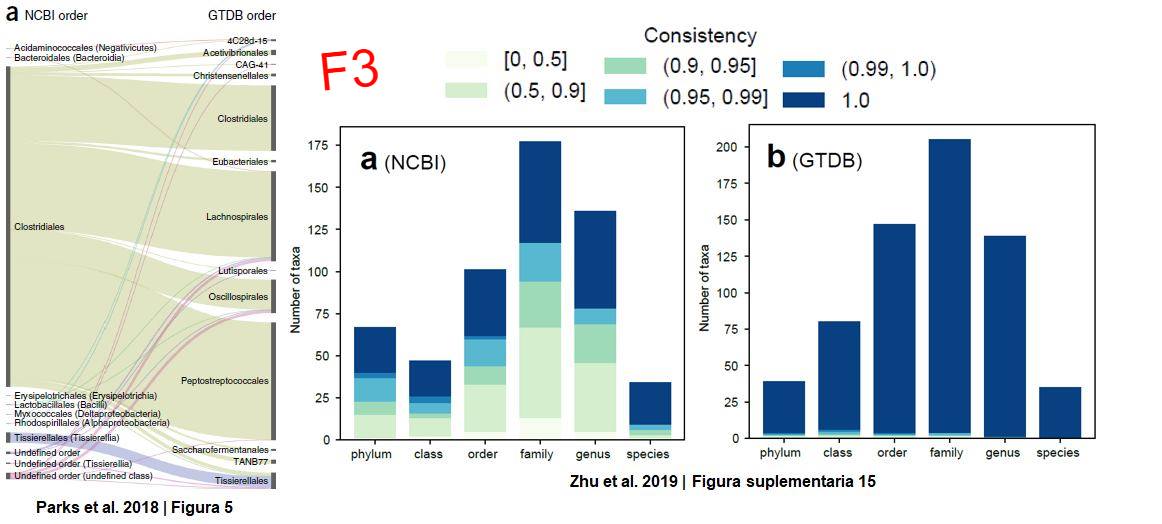

NCBI’s taxonomy uses a polyphasic approach based solely on experimental evidence. However, it has been shown to have many groups of prokaryotes with unresolved taxonomic relationships (polyphyletic groups) and does not include all the diversity of microorganisms that has been discovered through massive sequencing, which could lead to erroneous conclusions regarding organism classification (F3). The problem here is: what resource to use to classify all forms of life? (Figure 1 = F1 in the images)

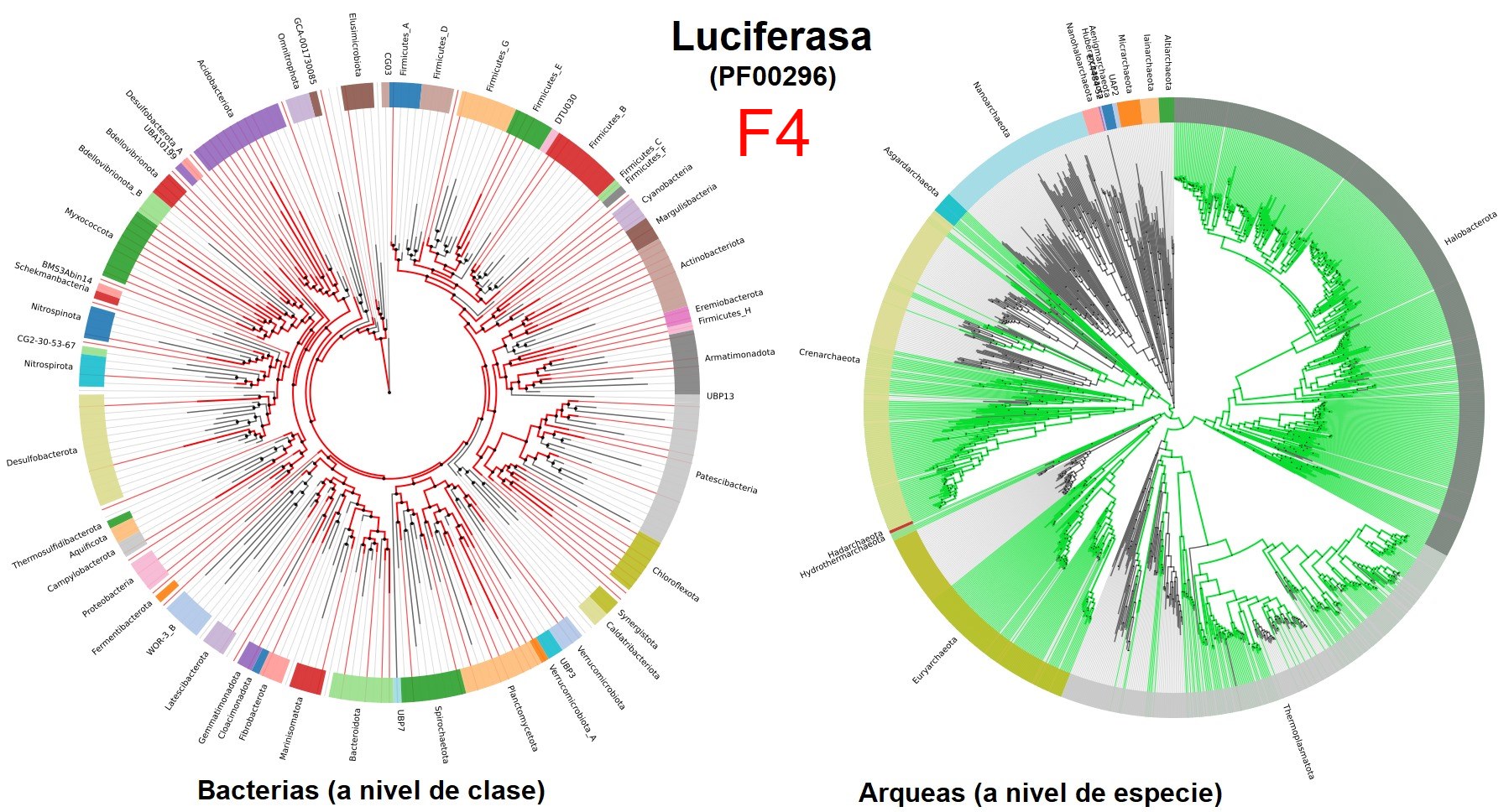

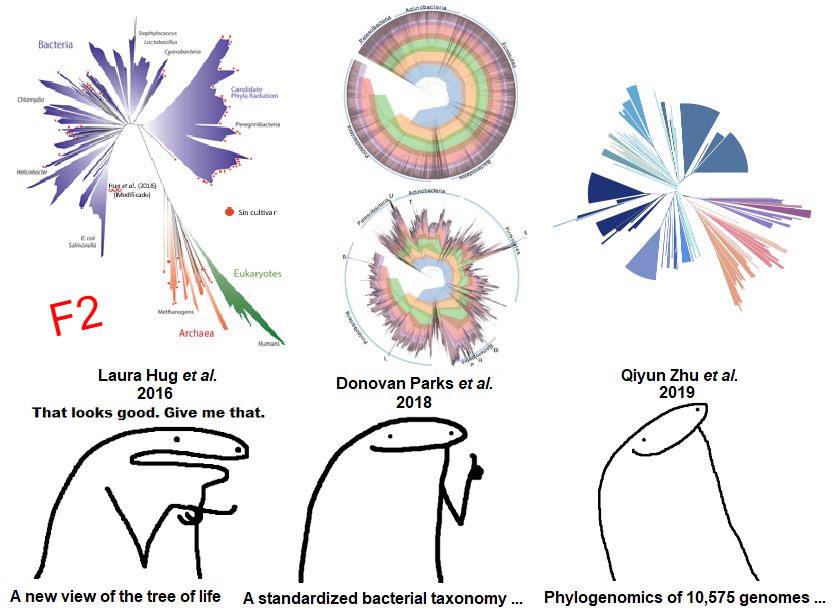

Laura Hug et al. demonstrated that, with 16 single-copy genes, mostly ribosomal genes, it is possible to classify prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. However, they did not address the problem of polyphyletic relationships of prokaryotes. In 2018, Parks et al. presented the GTDB, where using 120 and 122 single-copy genes for bacteria and archaea, respectively, it is possible to classify the vast majority of prokaryotes in a more precise way than the previous two. I consider GTDB to be a very well-made database that also has several very useful tools such as the AnnoTree page where anyone with basic knowledge of biology and a bit of genomics can search for genes in all known prokaryotic species so far, for example with the luciferase enzyme domain famous for being responsible for bioluminescence in several creatures (F4). However, one of its biggest criticisms is that many of the groups with polyphyletic relationships in NCBI had to be moved, coupled with the idea of trying to standardize biodiversity with biomathematical parameters (F3).

In December of this year, Zhu et al. present one of the most robust works I have read so far, where using 381 single-copy genes they reinforce the proposal that it is necessary to update NCBI or, alternatively, to use classifications such as GTDB or WoL (Reference Phylogeny for Bacterial and Archaeal Genomes) developed in their work, which is actually quite congruent with the classifications proposed by GTDB (F3, notice the consistency index where the closer to 1, the greater the congruence in classifications). However, the main conclusion of the work is that, using this set of genes, the relationships between bacteria and archaea change, going from being organisms with a considerable phylogenetic distance as seen in the separation of the branches of Laura Hug et al.’s tree, to being organisms that are actually closer than previously thought, an idea that changes what we have believed for ~12 years. This is because apparently ribosomal genes alone seem to be subject to greater evolutionary forces than the rest of the genes between archaea and bacteria.

In summary, we still don’t know what’s going on with classifying life

Refs: